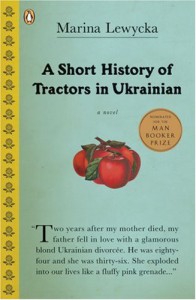

A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian

“A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian”by Marina Lewycka

Were we to spend 30 to 40 years of our lives without meeting a single Ukrainian, and be unaware that their communities are dotted about the country, the revelation of their existence would come as little surprise. We've heard tell of Somali social clubs going back a century, personally we know shed-loads of Poles, we sit next to Brazilians on the bus or train every day. The UK is a peculiar sort of place. Funny, too. Its native humour is interlaced with the self-parodies of the Pakistani, Yahudi, Italian, Chinese and German types who over the years have made it their home. Such diversity began long long before the post-war immigration boom, by which time the UK already had its panoply of national stereo-goons: the Welsh teachers, Canadian adventurers, Irish nurses, Australian sheep farmers, English toffs, Caribbean sailors and Scottish housekeepers. So if now we've got Ukrainians too, it figures.When people say, as they do, there's something very English about... and then go on to yak about something that is not at all English indeed, we nod and accept these as facts because so often there's truth in them. There's something very English, we say, about the Turkish kebabs on every high street, just as there's something terribly English about curry. There's something quite English about trusting a plumber because he's Polish, well they do work harder and invite you to haggle if you think they're overcharging. There's something absolutely English about the rise and fall of the Asian mini-mart; and then campaigns to save our Chinese laundries, Italian ice-cream parlours and French onion sellers are just about English as you can get. Though the English invented class snobbery, there's something utterly English about the young aristocratic lady in Downton marrying the Sinn Fein chauffeur.Therefore, to say there's something very Engish about “A Short History of Tractors In Ukrainian” is not to annex beetroot soup, fur-lined caps or Natashas with embossed fingernails for the British Empire. It's to say that this story of Ukrainians in Peterborough is an archetype in a post-modern world of which the UK has become capital.

Of course, apart from the Crimean War (1853-5) a while ago there was little to connect Britain with the former Soviet Republic, and what is least English about the book is how the Mayevskyj family became slave workers under the Third Reich, then refugees after World War Two. The British were not overly concerned in the tragedies that befell former provinces of the Romanov empire, preferring to mop up after the Ottomans. Things began to change after the fall of Poland in 1939. In the seven decades since, it's fair to say that population-wise Britain has become the most European of all EU members, leaving aside its aloofness from the Euro project. What distinguishes the UK is not simply the sheer number of emigrés it has absorbed, but their diversity and the endurance of their cultural values. With alacrity, the UK celebrates its very own Hungarian bean-fests and Romanian Independence days.“A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian” is the story of how a septuagenarian engineer, Nicolai Mayevskyj, betroths a thirty-something Russian divorcée from the Ukraine, Valentina, and what his daughters Vera and Nadezhda - our narrtor – go through. It's partially a comic novel with the line “I have a cunning plan” - Baldrick's catchphrase from “Black Adder” - repeated no less than three times. The fun-poking at Nokolai's one-foot-in-the-grave search for companionship and Valentina's boil-in-the-bag modernity is interspersed with chunks of family history, sibling rivalry between Vera and Nadezhda, and memories of their dead mother.

Actually, though the writing never ceases to be light, it is seldom lightweight. Through the medium of English and English slapstick, things Ukrainian and Russian are presented effortlessly and with charm. Whenever the action descends into parody and farce - over Pappa's “squishy-squashy” impotence for instance - the narrative takes a sudden twist and we're treated to a chapter from his on-going manuscript history of Ukrainian tractors.Marina Lewycka's use of tense is subtly done. Most of the action is told in present tenses, which gives the story-telling a button-holed, in-your-face quality. Some writers, Andrew Miller for example, carry the use of present tenses to extremes. Lewycka, however, frequently reverts to past tense narrative, sometimes even in the same scene, and once again the effect looks effortless. I had only a few quibbles with the text; sometimes there were double line-breaks between paragraphs in the same scene and I couldn't see why. Also, as with the Baldrick line, there is occasional over-use of repetition: “Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells” pops up two or three times more often than originality demands. And occasionally you get lines which could only be of benefit to non-native speakers, for example: “Now he is spent up – he has no money left.”

This is an easy and rewarding read which leaves me feeling intrigued and keen to read on. If I ever come across the volume advertised on the back cover - “Caravans” - I'd certainly consider buying it, if only to see if Lewycka extends her reach, or branches out beyond the world of Ukrainian emigrés.