Cottrell's Olivier

In a recent Guardian newspaper interview (6/5/2014), the poet John Cooper Clarke made fun of poets whose parents approved of their work,

I can read a poet now and tell within a few lines if they have been encouraged by their parents. You know the ones who have been told from an early age: "It's marvellous Tarquin." It's invariably rotten.

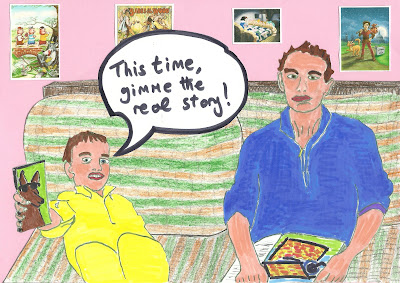

The same holds true, I believe, of actors. Leaving aside for one moment those from established Thespian families (the Redgraves and Fondas of this world), actors can easily be divided into individuals whose parents pushed them, and the rebels who had to jump ship to get into the business. That's not to say the likes of Dirk Bogarde or Toyah Wilcox turned into "rotten" actors, though there was a quality of self-satisfaction about their work which they needed to overcome. Lawrence Olivier came not from a theatrical background but from a High Anglican vicar father with an interest in the stage. By substituting religion for the theatre, Shakespeare for god, his single-parent upbringing and being sent off to drama school at the age of seventeen, we can appreciate how Olivier sprang from between two sources: sub-noble scion and gang-show bore. Bolted on to that, the early years of slogging at his craft and mixing with sundry Method actors (yes, John, there's always one hanging about), comedians and natural talents, Olivier honed himself into the greatest ham of all time.

This much, John Cottrell's book tells us, though never so directly. We could have expected a more in-depth analysis of the actor's psychological make-up from the writer of a "best-selling account of the assassination of President Kennedy". Instead we get copious notes on the false-noses, hair-dos, voice production and other externals that make up an actor's craft, along with some details on his career as empressario, then as first director of the Chichester Festival and National Theatres. Of his three marriages, four children (by two wives), home life, friendships and out-of-theatre interests, we get some snippets - though few of them choice or telling asides. The fact that Oliver was still very much alive when this biography was published (coinciding with his seventieth birthday; he was to go on living and working for another decade and more) seems to have inhibited not merely its content but its scope.

As a straight forward account of Laurence Olivier's progress from child actor to his elevation to the peerage (he was the first actor to be granted a seat in the UK's House of Lords), this biography does a tolerable job. Graduating from the Central School of Speech Training & Drama in 1924, the artist served an apprenticeship at Birmingham Rep and rose, within a few years, to become a juvenile lead in London's West End. He made early forays into talking pictures and by the close of the 1930s had established himself on both stage and screen both sides of the Atlantic. His partnership with Vivien Leigh (second wife) continued through and beyond World War Two with both taking starring roles in acclaimed films (she in “Gone With the Wind”, he in “Pride and Prejudice) and in stage productions (appearing together as Lord and Lady in “Macbeth”). He also followed his colleague Ralph Richardson into active service in the Fleet Air Arm as a pilot, though for most of the conflict he was seconded to the entertainment side of the war effort. His filmed versions of three Shakespeare plays (“Henry V”, “Richard III” & “Othello”) were considered milestones both for their use of the medium and for popularising English classical theatre. Olivier could turn his hand to a wide variety of roles and acting styles. For example, as he approached his fiftieth birthday, he was able to star alongside Marilyn Monroe in “The Prince and the Showgirl” (1956); then on stage as a fading music hall comedian in John Osborne's “The Entertainer” (1957, filmed in 1959). The 1960s saw a slight reduction in his stage and screen work as he took on the administrative role of directing the National Theatre, however he was still capable of turning out powerful stage performances, such as “Othello” and many cameo roles on film (for example, “Oh, What a Lovely War!”). This biography only goes up to 1976, when he had given up his twelve year stint at the National (while continuing to act for the company) , and had made films such as “Sleuth” (with Michael Caine) plus various TV roles (Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice” and Nikodemus in “The Life of Jesus Christ”).

It is not until page 350 (of a 480 page book) that we are told,

So often in the past he had been a law unto himself in his interpretation of a part, going his own unpredictable way to great personal advantage but sometimes at the expense of the production as a whole.

The year is 1963, the fourth decade of his professional career. Are we to assume that some of the failed productions were due to Olivier upstaging fellow actors? We are told the 1940 production of “Romeo And Juliet”, in which he and Vivien Leigh starred together, flopped when it reached Broadway. Why? Cottrell merely suggests the New York critics were prejudiced. That hardly explains why the couple who were about to star in a film together (as Nelson and Mrs Hamilton - a wartime triumph both sides of the pond) failed so spectacularly on stage. They had sunk their personal fortunes into the lavish production and done well enough on the road. They were, moreover, newlyweds and every bit as famous as Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor were to become two decades later. Without further exploration, we may be excused from wondering if Olivier - as Romeo - upstaged his Juliet. Or did Olivier lose his nerve? Without closer analysis we will never know, but it is the job of the biographer to do so.

In his penultimate chapter, Cottrell singles out Olivier's physical fitness and physical presence as two of his major strengths. He goes on to catalogue injuries he sustained both on stage and in front of the camera, including thrust and slash wounds from swords, an arrow in the leg, a broken ankle and electric shock. At times he would throw himself about the stage in unrehearsed business, and at others he would routinely perform leaps and bounds – at one time, after a bracket had broken, being left dangling ten metres above the stage from a piano wire. All of which suggests a recklessness which is at somewhat at odds with the man's conservative image. Indeed, it seems Olivier was that rare animal, the old school revolutionary. Never wishing to appear “old hat” (a favourite phrase) he would embrace the unconventional. Cottrell presents evidence to support the idea he was in fact rather awkward at times and that - though fond of grand japes - his behaviour could be either ungraceful or downright clottish. On his first day of operational duty at the Fleet Air Arm, he was taxiing a seaplane across the tarmac when he crashed it into two other planes, knocking all three out of action. One evening at the National, he gave such a tour-de-force performance of Othello that the whole cast lined the corridor to his dressing room, cheering him as he went by. He strutted past them and slammed the door behind him. Apparently he was upset because he knew he could never repeat the performance. To behave with such gracelessness before his fellows seems at best a lack of feeling, at worst the antics of a callous boor. While he so often excelled in stage charisma was he sometimes weak in self awareness?

There are precious few anecdotes in this biography, concentrating as it does on the actor/manager's successes and failures. We are told of his friendship with Richardson but only once do we see really them together, when Olivier was taken for a spin in his friend's new car, along with his new wife. The joke is funny enough but on its own does not amount to a portrait of their relationship. The rest is exchanges of advice here and there. You are left speculating perhaps the pair were not really friends at all, that there might have been more rivalry than companionship between them. So Cottrell doesn't really pursue Olivier the man. In the last chapters we learn he had a temper, but were are the shouting matches with Kenneth Tynan? And what were they about? Why was he so irascible at times? Did he drink too much? And what really happened between him and Vivien Leigh? I'm not tempted to say this biography asks more questions than it answers. The real problem is, it questions too little of Olivier's life and work.

I read this book out of two rather joyless motives: researching the Whodunit genre and the Second Novel. Another reason for reading was more whimsical: having seen plenty of Agatha Christie on screen, I'd never actually sat down and finished one of her tomes. And sit down I did, getting through the book's 200 oddish pages in two longish sessions. It was very readable, not particularly challenging, sometimes charming and occasionally annoying. In other words, it did what it said it would do on the box.

The characters Tommy and Tuppence are young, amiable almost-rogues who set out - circa 1919 - looking for remunerative adventure. Quickly, they get themselves embroiled in a plot, à la Zinoviev letter, to use the Labour movement to bring down the government. It's written from a mildly reactionary viewpoint, which mildly outrages me. The plot is far fetched and inevitably (for the genre) convoluted, but managed well enough and by changes of location, character and tone kept this jaded reader turning the page.

Let's see now, what's it got? Mystery a-plenty (if a-wishy-washy), crooked spies, red herrings, double-dealers, guns'n'poisons, the very prototype of the young assistant, romance, hard-boiled dialogue, hostage-taking, country houses, a millionaire with money to burn. No bumbling police, though; a shoot-out but no corpses; London scenes, but no pea-souper. I suppose you can't have everything.

Tommy and Tuppence, a couple whose first outing this is, were Christie's least commercially successful sleuths. I wonder if there isn't something too self-satisfied about a romantic couple's working together to make superstars of them like Miss Marple and Poirot? Perhaps one of these erotica hacks should take them on, insert bedroom scenes every ten pages and make a million dollars? Heck, it's outta copyright...

Sylvia & Michael by Compton Mackenzie

Sylvia & Michael

The Later Adventures

of Sylvia Scarlett

by Compton Mackenzie

I can only deplore the auto-backslapping of certain adventure writers that spend the last quarter of a book congratulating themselves on what a grand old tale they have told us. This pompousness kills half the suspense. "Sylvia & Michael" being the fourth, if shortest, volume of Mackenzie's romantic adventures of Michael Fane and Sylvia Scarlett, I'm afraid smugness pervades the whole tome.

Reminiscent of Kipling's "Kim" and Scott's "Heart of Midlothian" in this, and one other respect, the hero and heroine's fates are plotted against huge events that dwarf the sum of all the individuals involved. Sadly, when Mackenzie sat down to write "Youth's Encounter" (vol. 1 of "Sinister Street") he could have only an inkling that the final dénouement of his story would take place in the midst of what would become known as The Great War, and then the First World War. Yet drawing so heavily on his own experience of public school, Oxford university, the Anglo-Catholic branch of the Church of England, Music Hall Theatre and the seedier side of Edwardian London, it is little wonder he employs his wartime experience in the Balkans and Eastern Aegean to backdrop and populate the scene of Michael's epiphany.

War, which breaks out while Sylvia is delerious with typhoid in Russia, puts people into uniform; which as Mackenzie tell us on the title page, makes every one look alike; except for the women, I suppose? Notwithstanding this, he claims there are no 'portraits' in the book. Of characters, then, there is the usual mix of vamps and scamps: the good, the bad and the very bad. Concetta makes a reappearance, persued by the evil juggler Zozo. Her fate is still as unfortunate as before and mirrors Lily, of whom there is no more news. There is a friendly Bulgarian bandit, an English Petroleum baron and an accomodating priest. All stereotypes must have their origin in the real world and, rather despite his claim, I imagine Compton Mackenzie was one of those people you would be wary of meeting lest he put you into one of his books.

Though a good deal of action goes on in the background, as it were, most of these adventures are of the soul. We have the predicatable dose of Catholicism - Roman, this time - intruding, somewhat incongruously into Sylvia's story. Not that her reversion to the mother church isn't sufficiently explained away, exhaustively in fact. It's just that I object to a story-teller using his own particular convictions as material in this way. Much better, I thought, was Mackenzie's account (in "Galippolli Memories") of his time on the shrapnel raked beaches of Turkey, when he felt in the hands of God and strangely at peace with his fate. In "Sylvia and Michael" we are asked to believe the couple witness some pretty awful atrocities - the ethnic cleansing of modern parlance - without feeling much more than their own good fortune. Still, I suppose, there may be a deal of the writer's experience talking there. I hope I never live to see for myself what war really is.

Going back to the other point about Kipling and Scott, if I may, there is an English smugness here, an imperious view. All the Serbs, Romanians, Bulgars, Russians, Greeks and what have you appear as so much flotsam on their own shores. There is a pervasive class snobbery, too; and despite the boyish character of liberated Sylvia, sexism. Wherever the plot roams, there is always a common cockney girl, whether pay-to-dancer or guesthouse proprietress, who is salt-of-the-earth.

I wonder at Mackenzie's Englishness. At one point in the book, he appears to criticise Erskine Childers' novel "Riddle of the Sands" for giving away secrets to the Bosch. That's rich! After the war, both of these distinguished writers turned to Celtic nationalism.

The ending of a saga must come as a kind of anti-climax. So much has gone before, the dénouement can hardly be organic. We must leave the world the author has created with at least a tinge of regret. And, perhaps, a slap on our own backs for having read so far.

Sylvia Scarlett by Compton Mackenzie

“Sylvia Scarlett”, one of the continuations in Mackenzie's “Sinister Street” saga, prompts a little backstory-telling. The eponymous heroine appeared in the first book of the series as self-appointed guardian of Lily Haden, whom Michael Fane is in love with. Roughly at the same age, Sylvia and Lily are a couple of prozzies. Having baldly stated the fact, there is some further qualification of Ms. Scarlett's character: neither she nor Lily have much of the street-walking hooker in them. As Sylvia has already said to Fane (it is repeated here), “Money is necessary sometimes, you know.” These two educated and cultured young women inhabit the Imagist, Edwardian London of Ezra Pound (parodied here as the Languedoc poetester “Hezekiah Penny”). The company they keep is that particularly Kensington blend of low life fraudsters, single mammas, pseudo artists and young men of the Oxbridge set. It is a sort of West London version of the Bloomsbury group, except that for politics you should substitute religion; and for theatre, music hall.

Considered extremely daring at the time of publication (1918 for “THE EARLY LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF SYLVIA SCARLETT”, to give its full title) this saga can sensibly be compared with contemporary works by James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence. Whereby Mackenzie was adept at sailing as close as possible to the moral wind of the day, he managed to benefit from the publicity stirred up by outrage. At the same time he avoided the censure of the law without being shunned by the book-buying (if not the book-borrowing) public. In short, his tomes sold like hot cakes in a society increasingly obsessed by sex.

Whereas the adventures of “Sylvia Scarlett” are not as a poetically or lengthily written out as those of Michael Fane, her complete life up to the age of thirty is emcompassed, with much glossed over. The scenes with Michael and Lily, for example, which take place as the characters are in their early twenties, form only a short (if crucial) part of this narrative. And to what extent we are given a fully rounded, believable portrait of this young woman is debatable. When loosely filmed in 1935, with a tom-boyish Katherine Hepburn (as Syvia) and the super-dapper Cary Grant (as Jimmy Monkley), cross-dressing was used to much stronger effect than here. There is an obvious homosexual interpretation but, like a tamer version of Evelyn Waugh, Mackenzie merely dangles the possibility in front of his audience; for instance, at one point telling us that Sylvia's hands are masculine.

Sylvia's clear protoypes are Fanny Hill and Becky Sharp (the latter also filmed in 1935). She is her own woman from the start, and while she frequently throws herself on the kindness of strangers, she always manages to rise above the kind of squalor normally associated with frausters amd common prostitutes. This is despite not being a great beauty herself.

Still as a teenager, she is married (to an Oxford man) and divorced. She frequently walks out on money and prosperity because foremost in her mind is being true to herself and never to be groomed (“developed” is the word often deployed here) to suit another's whims. This doesn't stop her from grooming others, most notably Lily and Arthur Madden. The reader is treated at fairly regular intervals to solliloquies in which she, in something like a stream of consciousness, sums up her situation. For example, in a long paragraph beginning with the words “I must be getting old...” (she is twenty eight at the time) she compares herself, favourably, to a drunk, because, “drunkenness is the apotheosis of the individual”.

Later on, when facing the imminent prospect of marriage she tells a close friend that really she is no feminist, “...Personally I think that the Turks are wiser about women than we are; I think the majority of women are only fit for the harem and I’m not sure that the majority wouldn’t be much happier under such conditions. The incurable vanity of man, however, has removed us from our seclusion to admire his antics, and it’s too late to start shutting us up in a box now. Woman never thought of equality with man until he put the notion into her head.”

Having started life in France (she is only half English) she spends her teens in England then travels in Italy, Spain, Morocco, South America and the USA. By her mid-twenties, she seems to have given up the life of the working girl and turned instead to the family tradition of musical theatre as both her principal means of living and her means of fulfilling a creative urge. Throughout these novels we are given to believe the borderlines between fraud, musical theatre and prostitution are very thin indeed. Mackenzie himself grew up in a theatrical family, and the fame of his sister Fay Compton still survives in living memory at the time I write (2013). Presumably he knew his subject far better than he dares equate us.

The book abounds in piquant adventures. At one point Sylvia becomes the moll of an Argentine gangster with whom she escapes from a shoot-out in a bordello. At the same time, we are asked to believe her relationship with Carlos Morera is platonic and that he showers her with valuable presents (setting her up for several years to come) for the mere pleasure of escorting her round town.

Mackenzie does not subject Sylvia to the thorns of her many rose beds. Whatever ups and downs his heroine endures barely scratch the surface of this oh-so wise and cynical woman-child. And whenever she comes across characters whose fates are without her good fortune, she is able to look on with more sympathy than empathy. Concetta (a dancer) and Rodrigo (a guide) whom she meets in Granada, are in situations not unlike those she has been through herself. Yet as she is about to help them, one is abducted by a jealous lover while the other is fatally stabbed by a rival. Back in London she is shocked to hear that Jenny Pearl, the model of an artist friend, has been shot dead by her jealous husband. But this promises to be merely a plot device. In fact, Sylvia's character can be callous or even craven at times. For example when Jimmy Monkley, who took care of her after her father's suicide and who has been gaoled for fraud, comes out of prison to visit her, she flees for her life. At the time, she is riding high on the success of her musical show - but in horror of the past, overlooks the debt she owes him. Actually, survival instinct is in operation here and we can't blame Sylvia for shutting the trickster Monkley out. He was grooming her when she left him at the age of fifteen. But it convenient to be able to choose what you will of your past life, a luxury not afforded to most of the characters here, or in real life for that matter.

Even after her most crushing reversal (I won't reveal just what) Sylvia is able to dust herself off and, pocketing a timely windfall, escape from the consequences.

This is a story that does not end on the last page, though it says “THE END” in capital letters. Throughout this volume there are references to Miachael Fane and, who'd have guessed, it was followed up by “SYLVIA & MICHAEL - THE LATER ADVENTURES OF SYLVIA SCARLETT” in 1919, a book even shorter again. If there are diminishing returns in the series, more fool the reader (me, for example) hanging on in to the bittersweet end.

A note about religion: Sylvia, it is made plain from time to time, is a woman without religious faith. Mackenzie, however, cannot resist inserting a chapter mostly devoted to the pro- and anti- anglo-catholic schisms in the Church of England. He achieves this with skill and not a little entertainment à la Lurch in The Church. He even manages to get the non-believing Sylvia to come down on the side of his own pro-ritual views. The gauntlet thrown down by Joyce in "Portrait of the artist as a Young Man" is picked up.

"Dispatches" by Michael Herr

Meet Murder: Revisiting Michael Herr's “Dispatches”

To my younger eyes, the film “Apocalypse Now” was somewhat pretentious. It had eventually came out not long after I finished reading Michael Herr's book “Dispatches”... but a while before I finally got round to Conrad's “Heart of Darkness”. I supposed there was some subtlety in Francis Ford Coppola's film that I was missing, since he had reportedly based his script on a fusion of those two books.

I next viewed the film a couple of decades later, by which time I had done my Conrad reading, and realised it was Marlon Brando's pretentious portrayal of Kurtz that had spoilt the show... and not the film's ambitious blending of fact and fiction. Martin Sheen, Dennis Hopper and even FF Coppola himself were vindicated. Marlon had become a fat slob, a bloated angel unworthy even of the messianic Kurtz role.

Every bit as chilling as Capote's “In Cold Blood”, “Dispatches” brought the corpse of America's Vietnam war back to life to my generation. We had all too quickly moved on. Just when we were beginning to forget the horror, Herr came and jolted us out of our safe European punk rock fantasy world. One of the many telling images he gives is of a grunt he ran into a small jungle clearing. He had just gone to take and leak, but the young soldier seemed uptight to have him there,

“He told me that they guys were all sick of sitting around waiting and that he'd come out to see if he could draw a little fire. What a look we gave each other. I backed out of there fast, I didn't want to bother him while he was working.”

Read this book if you think “Full Metal Jacket” is pure entertainment, if you're not afraid to face the truth behind the statement, “Hell Sucks”.

Review of S.W. Persia by Sir Arnold Wilson

Sir Arnold Wilson is one of the most reviled characters in that strange unfinished enterprise, the British Empire. After the First World War he was put in charge of the territory that would become Iraq, where he soon became known as 'the Despot of Mess-pot'. Under his administration, riots were put down at a cost of 10,000 lives. While he favoured direct rule by the British, Gertrude Bell, his assistant, supported by TE Lawrence, believed the only solution was to make an Arab kingdom under Faisal, son of Hussein (Guardian of the Holy Mosques). Wilson eventually accepted the idea, but was replaced by Sir Percy Cox, his old boss at the Foreign Office of the Indian Government. Wilson was knighted and, in consolation for his loss of public office, was appointed a director of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (the precursor of BP). Later he became a Tory MP and during the 1930 gained a reputation as an apologist for Mussolini and even Adolf Hitler. However, he died fighting fascism at Dunkirk in 1940, aged 55. This book, 'S.E. Persia' – subtitled 'Letters and Diary of a Young Political Officer, 1907-1914' was published posthumously in 19411. He had written it while serving as an air gunner officer with RAF Bomber Command in the year that led up to his death.

Anyone with an interest in the history of the Middle East, especially if they have spent time in the area, will recognise the authenticity of this book. Wilson, who trained at Sandhurt and started his career as a map engineer in the Indian army, was made a liaison officer to accompany the Turko-Perso-Russian commission which was determining and mapping the eastern border between Iran (then known as Persia) and the Ottoman Empire. This meant surveying through tribal territories between the Shatt-al-Arab and Mount Ararat. It was the first time much of the area had been mapped using modern methods, and through Wilson's efforts the British gained invaluable intelligence. The need for the Turks, Persians and Russians to co-operate created an extraordinary opportunity for espionage that Wilson did not shrink from exploiting whenever he could.

At considerable risk to his own life, he employed knowledge of Arab and Persian dialects, a fearless belief in his right to be there, and the horse-trading skills of a native tribesman. The writing, especially in his letters to his family, often veers into the braggadocio of an earnest young Christian anxious to prove he is no heathen. Whenever he has the need to placate a local potentate, he hands out finely printed Korans as presents, buys up quantities of goats, has them slaughtered and then roasted to make propitiatory meals. According to him, the natives often look on this infidel with a certain awe – i.e. in the same regard we associate with Lawrence. In fact, if even half of these adventures are true, they make his more famous countryman's exploits look like those of a boy scout on some jolly jamboree. Wilson is not some mere orientalist with half his mind taken up by ancient ruins. His remit is as the agent of an increasingly oil-hungry empire. He looks on all foreigners as potential allies or enemies in the Great Game; and if he wonders now and then about the Kurdish or Zorastrian inhabitants of a forgotten village, it is seldom without the hint of how much more profitably they might live under the aegis of Pax Britannica.

At one point in his days as a young political officer, Wilson makes a journey home to visit his family in England. Instead of paying for a berth on board a steamer, he opts to work his passage as a stoker! When the ship calls in at Port Said to take on coal before entering the Suez Canal, he accompanies his fellow stokers to a brothel. I couldn't resist using this in 'My Heart Forgets To Beat', where I have Dic (the stoker of Swansea) befriending a version of Wilson and taking him to the house in the question. Other steamy details include the 'temporary wives' taken by the Bengal Lancers, Indian cavalrymen employed by the British in their occupation of southern Persia.

I don't think readers of this book will be converted into supporters of the British Empire, from which saints preserve us. But I do think a perusal of its anecdotes will help explain Britain's continuing embroilment in – and fascination with - the Persian Gulf.

(I) First published by OUP, I have the hardback Readers Union edition of 1942.

Literary analysis of Radio Four's longest running Weather Broadcast

http://downwritefiction.blogspot.com/2013/05/a-shipping-forecast.html

1

1